Jolliness and Insights in Zen Stories

Laughing Buddha. Image: Patrick Seguin on Unsplash

The wisdom traditions of the East recognize our all too human tendencies toward sensual desire, ill will, sloth and torpor, agitation and worry, and doubt; five hindrances that keep us in a permanent state of fear and distress.

They also recognize that the root causes of our collective human predicament are to be found deep in our subconscious; in the emotionally learned patterns we acquired before we learned language. Therefore, when these patterns become a hindrance later in life, in no way can they be reached by means of our cognition, or intellect. For that reason the Eastern traditions sought various methods to speak directly to our heart, which is to say that they appeal directly to our emotional intelligence.

Zen Buddhism originated in China as a marriage between Mahayana Buddhism from India and Taoism from China. In a broad way, we can state that Mahayana Buddhism offers ways of liberation (from our monkey mind) through extensive self-knowledge; Taoism offers ways of liberation through intimate knowledge of – and experiencing ourselves as – Nature; and Zen Buddhism offers ways of liberation through experiencing the world directly, which is to say before we name, categorize, and label our experiences.

Of these wisdom traditions, Zen particularly attempts to bypass our intellect by appealing directly to the core of our being, which some call ‘soul’, others ‘intuition’, or what the ancient Chinese called xīn (心). The word xīn refers to the both the heart (emotion) and mind (cognition) since they were not considered as separate, but rather as coextensive: the heart-mind.

In other words, Zen texts and stories aim at an intuitive, emotional reaction, instead of gaining intellectual knowledge. In fact, as soon as we proclaim to have understood a Zen text, a Zen master will most likely hit us with a stick and tell us to go back and do our homework, because we fell into our well known trap to rationally explain the text in question.

A better approach towards Zen texts can be found in the ‘getting’ of a joke. When a joke is told, we either get the punchline right away which makes us laugh, or we don’t get it which makes us feel silly. Zen texts work in the same fashion: we either get them or we don’t. And in order to get them, we have to be ‘in the know,’ just like we need to be in the know about the different lines of thought which are combined in a joke.

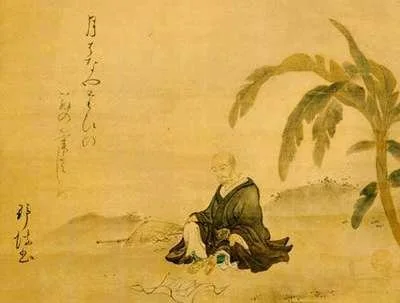

A forest pond.

A frog jumps in.

Plop.[1]

Basho and the frog. Image found on allpoetry.com

Zen uses what there is instead of what we think or believe or wish there is. For thinking, wishing, and believing, all belong to the realm of our intellect, which, when it comes to acquiring a peaceful and joyful state of mind, is more of a hindrance then a help. Zen stories, therefore, have an effect only when they’re felt, rather than when they’re cognitively understood.

Take Hold Of Empty Space

Sekkyo asked one of his accomplished monks, “Can you take hold of empty space?”

“Yes, sir,” he replied.

“Show me how you do it.”

The monk stretched out his arm and clutched at empty space.

Sekkyo said, “Is that the way? But after all you have not got anything.”

“What then,” asked the monk, “is your way?”

The master straightaway took hold of the monk’s nose and gave it a hard pull, which made the latter exclaim: “Oh, oh, how hard you pull at my nose! You are hurting me terribly!”

“That is the way to have hold of empty space,” said the master.[2]

Another fun aspect of Zen is that Zen masters often urge their students to talk or think as little about Zen as possible. The reason is obvious: talking and thinking belong to our intellectual realm, and if there is anything as far away removed from that realm, it’s Zen. The Zen Master Baiyun was known for stating that what can be said but not practiced is better not said. Therefore, as a rule of thumb, we can state that the more we think or talk about Zen, the less we understand it.

The Old Woman In The Tea Shop

Hakuin, one of the great Zen teachers of all time, used to tell his pupils about an old woman who ran a tea shop, and who had, in his opinion, a rare understanding of Zen. The sceptical pupils, unable to believe what he told them, kept going to the tea shop to find out for themselves.

Whenever the woman saw them coming she could tell at once whether they had come for tea or to look into her grasp of Zen. If they came for tea, she would serve them graciously. If they came to investigate her grasp of Zen, she would beckon the pupils to come behind the screen. The instant they obeyed, she would strike them with a fire-poker. Nine out of ten of them could not escape her beating.

Richard Alpert, in spiritual circles better known as Ram Dass, often talked of the distinction between conventional reality and ultimate reality.

Conventional reality refers to the world we live in. It is called ‘conventional’ because it is based on conventions, which is another word for ‘agreements’. In other words, it is the reality that we humans have created by means of, among other things, language, because we need language to make agreements that we all understand.

Thus, in conventional reality, the world is divided between me and you, day and night, black and white, dark and light. Ultimate reality, on the other hand, refers to the wisdom that every thought, feeling, thing, or being, continuously changes into its opposite in a never-ending cycle of arising and passing away. We call that the circle of life.

Zen appeals to our sense of ultimate reality. There are no distinctions between opposites in that realm, for if everything ceaselessly changes into its opposite, how can any distinctions be made?

Even before His Majesty

The scarecrow does not remove

His plaited hat.[3]

Eastern Scarecrow. Image: Ye Shengtao

One of the funniest misconceptions about wisdom traditions is their apparent lack of practical applicability. Their philosophically high-brow, moralistic, or goody two-shoes ethics are supposedly not useful in today’s dog-eat-dog world, but it’s exactly our idea of such a world which keeps us in our well known perpetual state of fear and distress. In his book ‘A Fearless Heart’, Thupten Jinpa (translator for the Dalai Lama) makes a strong case that cultivating compassion – and making it our second nature and basic perspective – actually makes us more joyful and less stressful by learning to be more compassionate, both for others, but particularly for ourselves.

Right and Wrong

When Bankei held his seclusion-weeks of meditation, pupils from many parts of Japan came to attend. During one of these gatherings a pupil was caught stealing. The matter was reported to Bankei with the request that the culprit be expelled. Bankei ignored the case.

Later the pupil was caught in a similar act, and again Bankei disregarded the matter. This angered the other pupils, who drew up a petition asking for the dismissal of the thief, stating that otherwise they would leave in a body.

When Bankei had read the petition he called everyone before him. “You are wise,” he told them. “You know what is right and what is not right. You may go somewhere else to study if you wish, but this poor brother does not even know right from wrong. Who will teach him if I do not? I am going to keep him here even if all the rest of you leave.”

A torrent of tears cleaned the face of the brother who had stolen. All desire to steal had vanished.[4]

Zen masters are regarded as such, because they have transcended the world of conventional reality and have experienced for themselves the realm of ultimate reality. That means they can now freely move between both realms; a state Ram Dass refers to as the ability to keep your heart open in hell. By that he means that we can still compassionately empathize with all the suffering in the world (which happens in conventional reality), while our presence in ultimate reality prevents us from going completely bonkers from the insane amount of suffering that is happening at any given moment.

When such a state of being is achieved, and we experience the world as it really is, normal conventions that most people find important fall away. Fellow human beings become more important than our own personal possessions for instance, and our actions become increasingly less sensible to ‘normal’ people. However, since Zen masters’ (and all sages for that matter) knowledge of human psychology exceeds even that of the most learned psychiatrist by light years, they are much better able to predict the future than the rest of us. And the funny thing is: they don’t even care about that.

The Thief Who Became A Pupil

One evening as Shichiri Kojun was reciting sutras a thief with a sharp sword entered, demanding either his money or his life.

Shichiri told him: “Do not disturb me. You can find the money in that drawer.” Then he resumed his recitation.

A little while afterwards he stopped and called: “Don’t take it all. I need some to pay taxes with tomorrow.”

The intruder gathered up most of the money and started to leave. “Thank a person when you receive a gift,” Shichiri added. The man thanked him and made off.

A few days afterwards the fellow was caught and confessed, among others, the offence against Shichiri. When Shichiri was called as a witness he said: “This man is no thief, at least as far as I am concerned. I gave him the money and he thanked me for it.”

After he had finished his prison term, the man went to Shichiri and became his pupil.[5]

All the world’s greatest religions can effectively be called wisdom traditions, because also the esoteric writings in Christianity, Islam, and Judaism, like their counterparts in the East, credit self-knowledge as the highest virtue in the spiritual quest.[6] They all recognize that, far from being physical locations that we can only enter after we die, heaven and hell are created, manifested, and maintained, within each and every one of us by our minds.

In that sense, the wisdom traditions, with all their stories and scriptures, have more in common with psychology than anything else. For not only do they diagnose the illness adequately, but they come up with various methods to get to the place where the root causes of our misery and suffering can be found: deep, very deep in our subconscious – that place our intellect can never reach, try as it may.

The Gates Of Paradise

A soldier named Nobushige came to Hakuin, and asked: “Is there really a paradise and a hell?”

“Who are you?” inquired Hakuin.

“I am a samurai,” the warrior replied.

“You, a soldier!” exclaimed Hakuin. “What kind of ruler would have you as his guard? Your face looks like that of a beggar.”

Nobushige became so angry that he began to draw his sword, but Hakuin continued: “So you have a sword! Your weapon is probably much too dull to cut off my head.”

As Nobushige drew his sword Hakuin remarked: “Here open the doors of hell!”

At these words the samurai, perceiving the master’s discipline, sheathed his sword and bowed.

“Here open the gates of paradise,” said Hakuin.[7]

Gates to Heaven and Hell. Image: wir_sind_klein

Zen, as a wisdom tradition, attempts to open our eyes – all three of them – to the world as it is, both internally and externally. Therefore, it is said that when someone begins Zen training, mountains are mountains, and waters are waters. Halfway, mountains are no longer mountains, and waters are no longer waters. But when one has realized the truth of Zen, mountains are again mountains, and waters are again waters.

Plop.

[1] Haiku by Bashō (paraphrased by Alan Watts).

[2] A Zen story from An Introduction to Zen Buddhism by D.T. Suzuki

[3] Haiku by Dansui.

[4] From Zen Flesh, Zen Bones by Paul Reps.

[5] Ibid.

[6] In order to maintain the hierarchies that developed within these movements, the idea of self-knowledge, which implied a direct line between ourselves and God, had to be abolished. Because if we are our own priest, what need is there for any middleman?

[7] From Zen Flesh, Zen Bones by Paul Reps.

Share your way!

Dear reader, even though the process of finding of our own way in life can be a tough and difficult road to travel, everyone who gathers the courage to walk it shares the same view: they wouldn’t have it any other way. Have you broken free from conventional life to find your own way? Do you have a knack for writing and would you like to share your story via this website? Feel free to leave a comment or contact us via the contact form. We’d love to make our community grow!